The Permian Recordings

at Co-Lab Projects

Co-Lab Projects, Austin, Tx

Durational subterranean infrasonic sound recording - architectural installation

Photos by Ryan Thayer Davis

Twelve Artists and Installations to Watch at Austin Studio Tour 2022, Texas Monthly

By Michael Agresta

Glasstire’s Best of 2022, Glasstire.com

By Leslie Moody Castro

Sounds From the Depths of a Texas Oil Basin, Hyperallergic.com

Review by Jennifer Remenchik

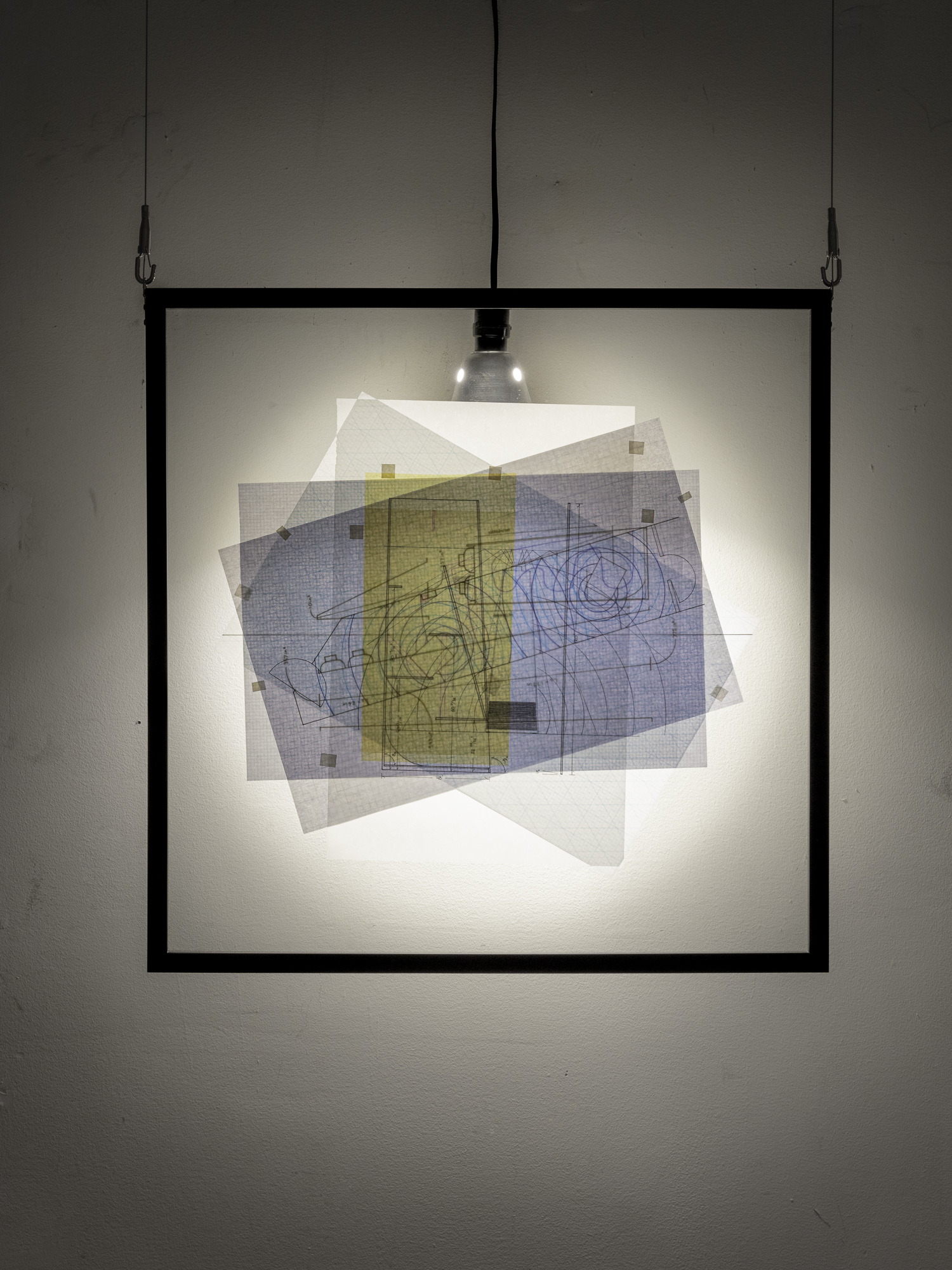

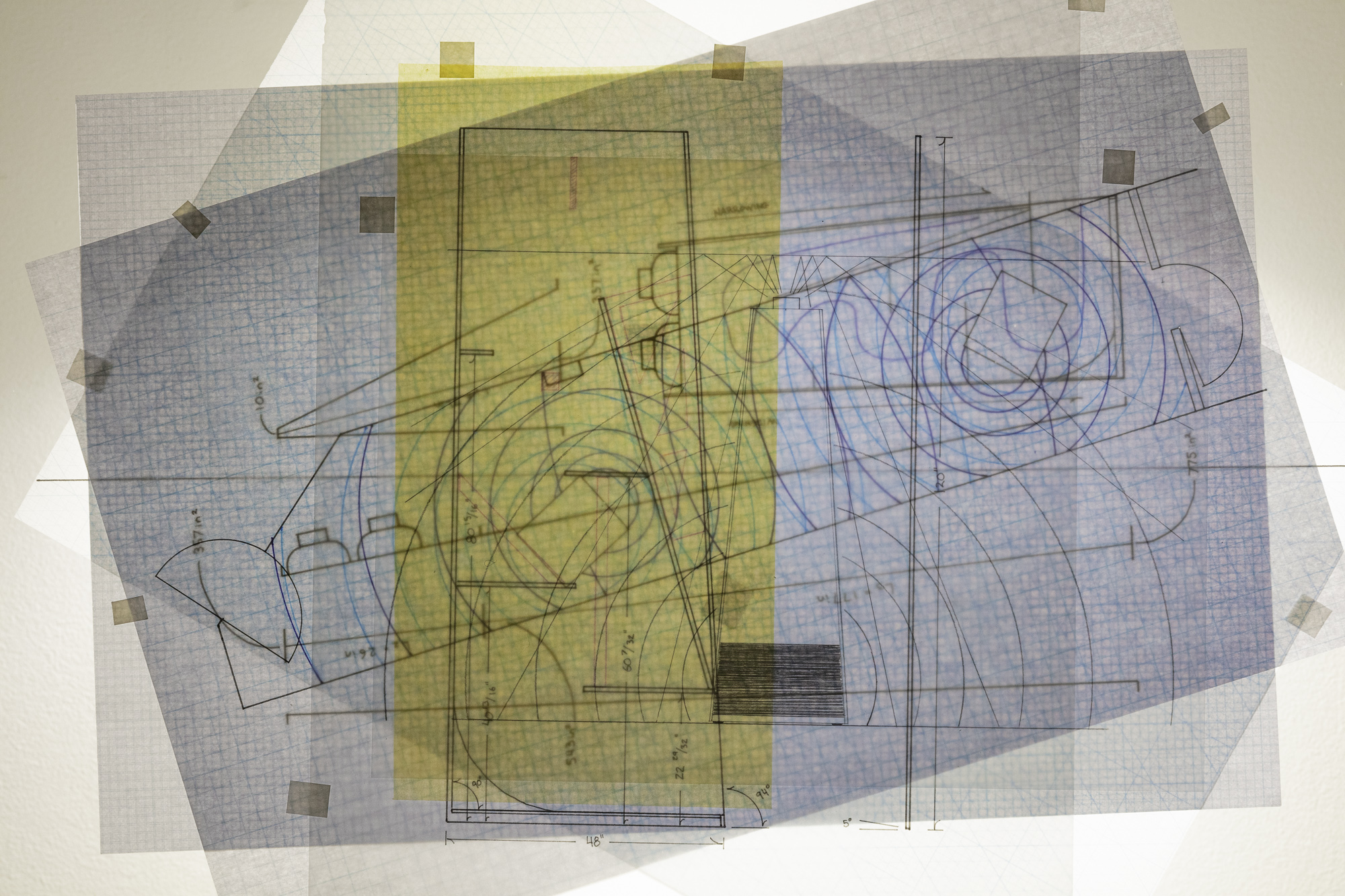

The Permian Recordings are a series of durational subterranean field recordings that capture the low-frequency vibrations of the Permian Basin in West Texas. This site-specific installation brings the recordings back to Texas for the first time. Exploiting Co-Lab’s unique concrete culvert, the piece turns the gallery into an enormous infrasonic subwoofer, a speaker at the scale of architecture. The low and infrasonic frequencies made possible by the architectural contours of the installation, cause the walls to pulse and shake in responce to the recordings. As in previous installations, the work brings into proximity two scales of time: the geologic and the biologic, expressing them not as irreconcilable measures of change, but as part of a continuum. In this specific installation, I imagine architecture as a bridge between the human and the geologic via the symbolic threshold at which foundation touches earth. Architecture is designed to be experienced in human time as the space we pass through and live within, and yet it endures, as in the ruins of our earliest structures, buried in dirt, a ligature to a distant past that simultaneously projects out into an uncertain future. Within this context, the concrete structure becomes a tuning fork on the surface of the earth, resonating with the frequencies of an industrialized landscape.

The Permian Basin is home to one of the world largest oil and gas extraction industries, while at the same time it is named for a geologic epoch whose end demarcates a period of catastrophic climate change and the largest mass extinction in the history of the earth. The frequencies in these recordings are both document and phenomenon: an aggregate of the hum of generators, the hammer of sand trucks down private roads, and the drone of drill bits churning invisible below the surface. How does one conceptualize a system so large in scope and consequence that it has passed over into the geologic? Standing in a field we hear the trucks and can count the towers and flares, but it’s only when we look down from satellites that we see the perfect grid of exhausted wells stretching for miles in all directions. But what of all we cannot see? The subterranean network of pipes and reservoirs, or the export of these mining technologies around the world, and of course the supply chain of oil whose thick black pipes that snake along roadsides throughout the permian eventually divide into the delicate vasculature that feeds every aspect of our individual lives? There is an anxiety in the infrasonic, a sound that is felt but unheard. These recordings extend from ancient rocks, passing through the structures we’ve built, and on into our bodies. Entering the speaker actualizes this connection, this linking of stone to flesh through the reverberations of architecture. Listening to these recordings from within the culvert, one is invited to sift through the acoustic strata and reflect on our connection to and participation in these larger terrestrial and climatic systems of which we are a constituent part spanning vast periods of time.

The Port of Long Beach Recordings

The Canary Test, Los Angeles, CA

Two-channel durational sound installation with infrasonic subwoofer towers

“Field recordings capture the subsurface vibrations of sand, surf, and distant cargo ships traversing America's largest port”

Photos by Paul Salveson

Phil Peters Bottles the Soundscape of the Global Supply Chain, Hyperallergic.com

Review by Renée Reizman

“As the sun sets over the Pacific, the Port of Long Beach continues to hum. Bright spotlights illuminate rows of towering yellow cranes processing containers from arriving ships. During the day, one can see the queue of cargo ships docked miles out into the ocean but as the sky darkens, they begin to disappear one by one.

The Port of Long Beach is often used to illustrate the huge scale and complexity of the global supply chain and in many ways, it is an ideal symbol; as the country’s largest port, the site symbolizes the modern, global economy.However, the visuality of this description undercuts its potency as a reference for the supply chain. The modern supply chain network functions on a massive temporal and spatial scale, defying traditional representation. Hence, the Port of Long Beach may metonymically represent the supply chain, but it is not itself the supply chain, just a mere node. This raises the question of how to describe the indescribable, an inherently aesthetic question.

Sound recordings provide one potential opportunity to resolve this bind. Sound is irreducible, a temporal process of constant layering, resonating, and negating such that any single, “pure” sound is difficult to isolate. To listen deeply is to be enveloped on all sides, divorced from the tricks of the eye. Though the backlog of cargo ships may slip into the Long Beach horizon, below the surface their churning engines continue to drone on, betraying their disappearance from the field of vision.

In his series of field recordings, Phil Peters uses this quality of sound to open a generative sensual experience. The recordings of the Long Beach Port make for a powerful and unsettling document of this logistical space. One can quickly make out the sounds of water gurgling but what gives the recordings their literal and metaphorical power is a deeper sound “heard” through the body with the aid of Peters’ imposing speakers, this sensory territory is made audible. While visual perception depends on a distance between the perceiving subject and the perceived object, there is no such distinction with sound, echoing Walter Benjamin’s description of Baudelaire’s writing: “The mass is so intrinsic to Baudelaire that in his writings one looks in vain for a description of it.” To hear the work is to be a part of the work.

As the aural territory of the Port, the recordings are not metonyms of this logistical node, they are the port. Once a listening subject is present, the work opens beyond documentation. In one sense, the work’s critical character could not exist without a listener through which the soundwaves can travel, paralleling the relationship of an individual to complex systems like the global supply chain. Global systems like this are near impossible to step outside of, to observe from an idealized, external perspective. Whether as producer or consumer, we are all caught in this web in some capacity. To attempt to study global networks at arm’s length, like studying a painting, precludes a defining trait, namely that there is no true external perspective. Without compromising the literality of the work itself, the experience of it slips into the allegorical language of global capital flows.

There is a danger in drawing these connections of overdetermining the recordings, boxing the ephemerality and limitlessness of sound within a single subjective interpretation. I bring this up to illustrate the slippery irreducibility of sound, as if discussing the work causes it to flee beyond interpretation. Peters’ sound works function critically precisely because they are neither moralizing nor didactic. In fact, they seem to precede language altogether, mirroring capitalism’s scale and expansion without becoming entangled in the murkiness of language. The recordings unlock new sensory perception, the rest is left to the listener.”

Responcive text written by Sampson Ohringer

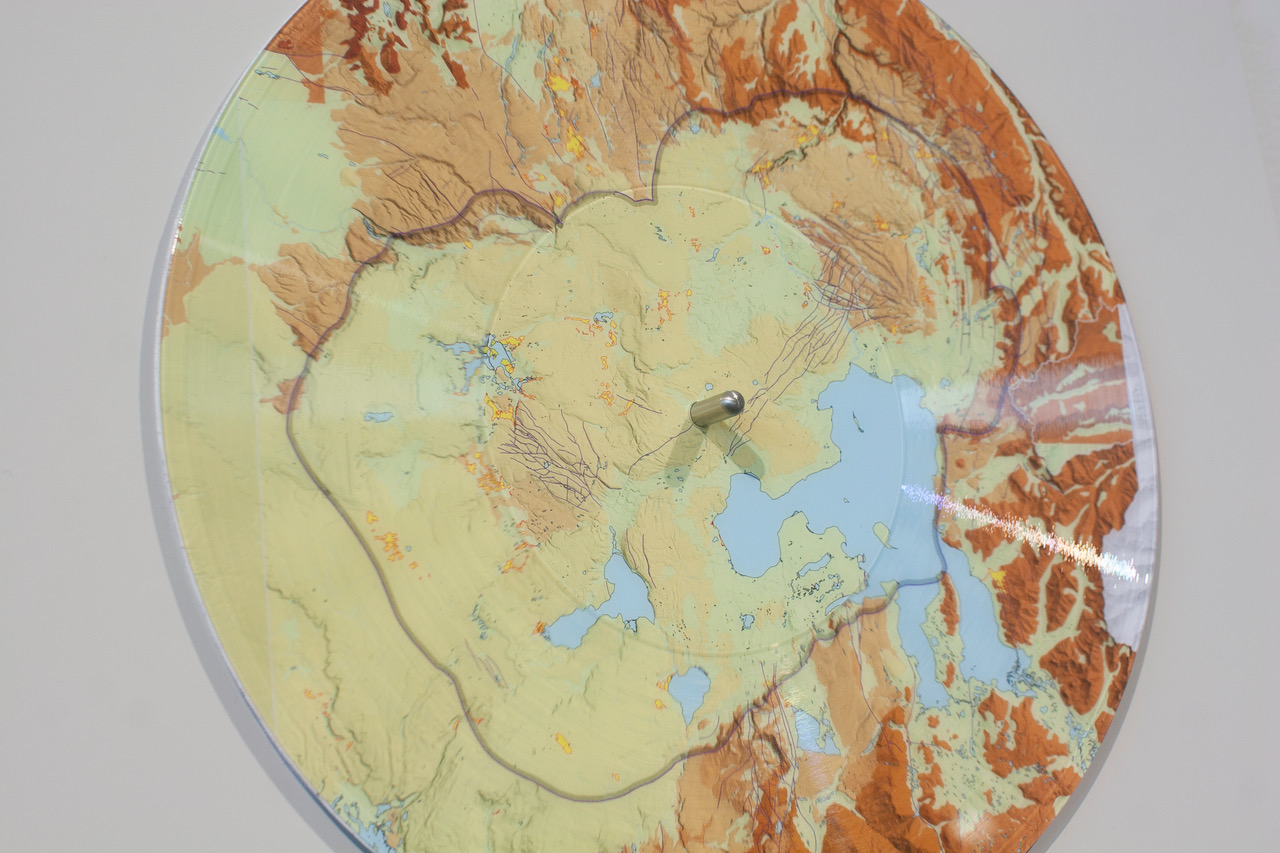

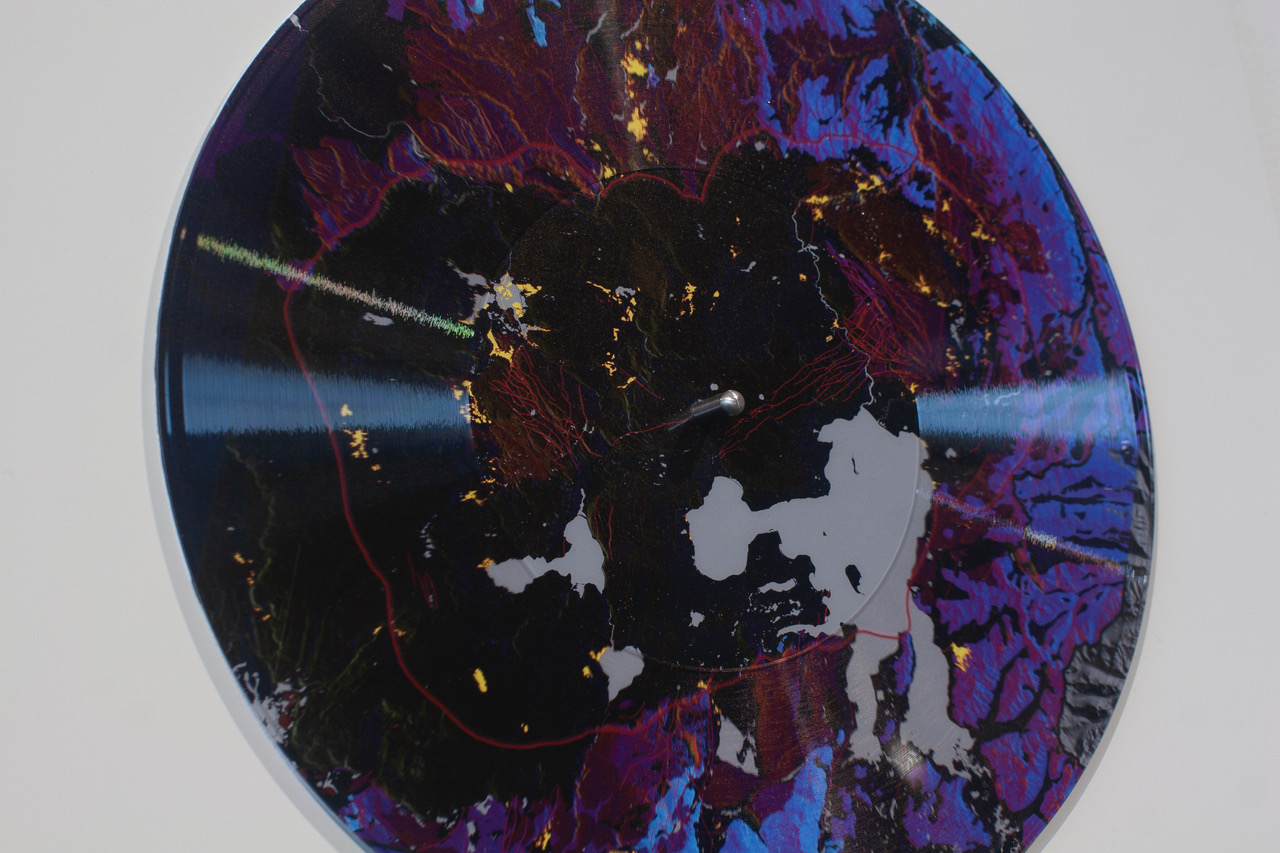

Volcanic Drift

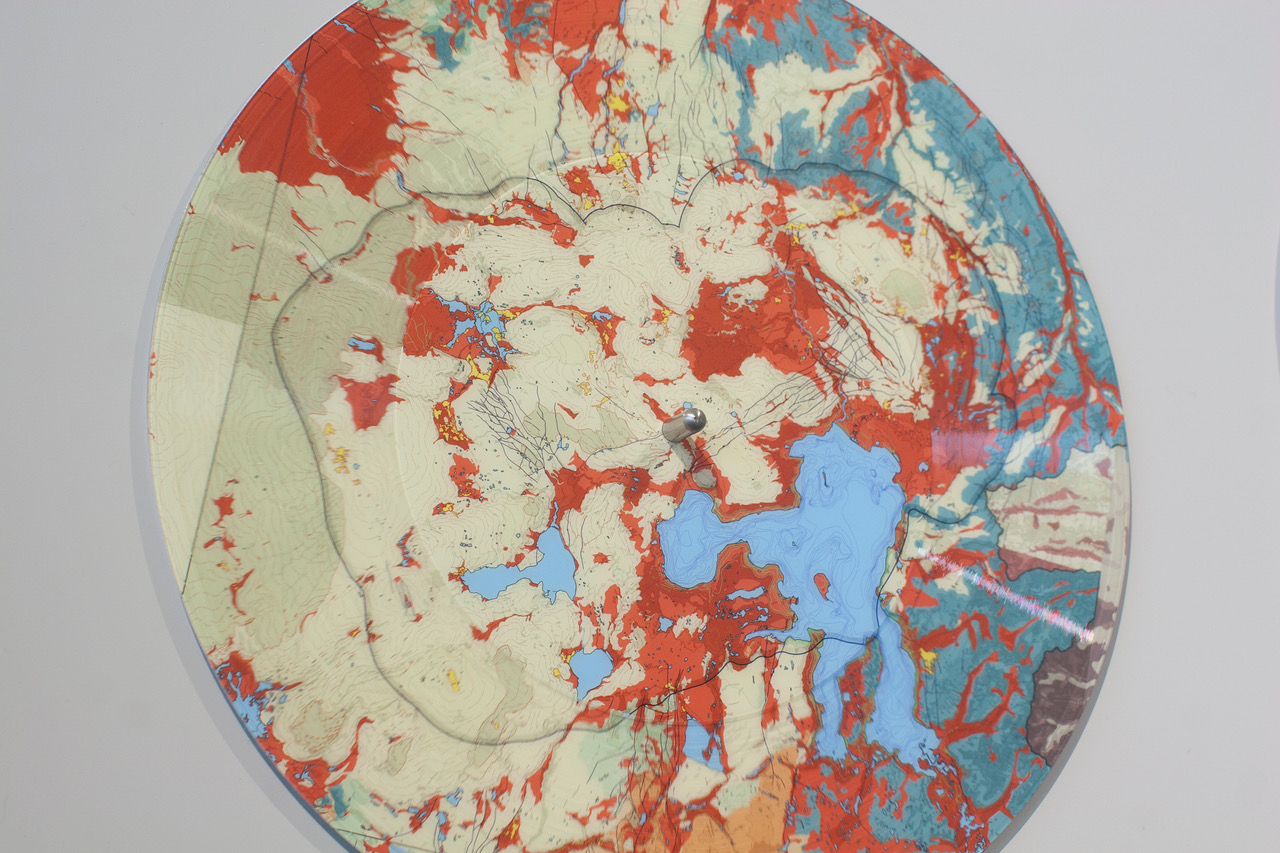

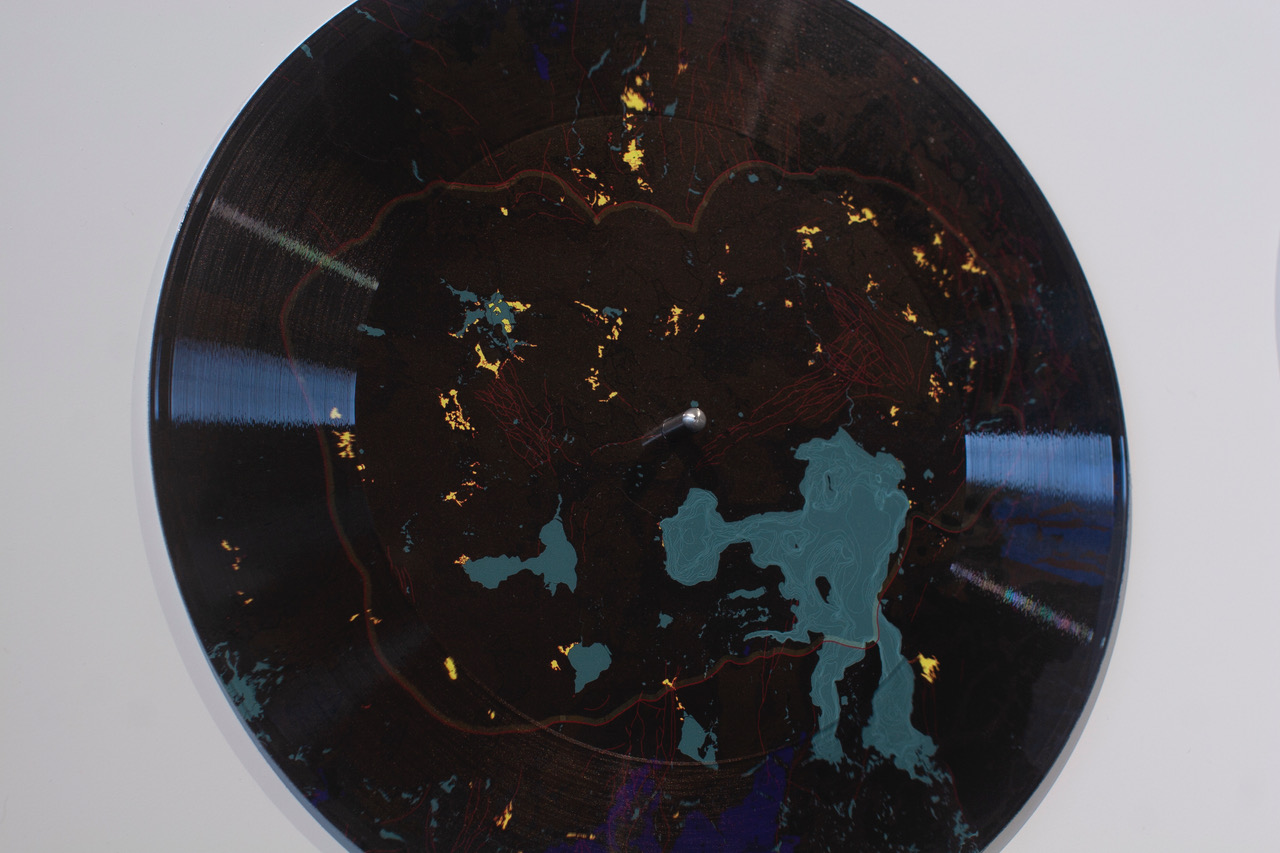

Volcanic Drift presents the subteranean sounds of Yellowstone’s super caldera, lathed into vinyl records, and played back through a pair of custom built subwoofers. Because a portion of this audio extends below the range of human hearing (the infrasonic), these recordings are felt as well as heard. To prevent the records from skipping, the turntable is mounted on a vibration dampening seismically stabalized pedestal designed to absorbe the architectural resonance.

This audio evokes the organic: coursing blood, a beating heart, steady breath. However, it belongs to a system so large as to be indifferent to organic needs. The shape is striated, like layers of sediment. In listening, as the sound drones on surrounding us, we are invited to sift through the acoustic strata, sinking into an alternate space. There is an anxiety here in the deepest layers of the infrasonic. It stems from cataclysm and the latent image of eruptive volcanoes and fractured earth, of burial but also a distant memory of birth. These recordings come from a place inaccessible and inhospitable to our bodies, and in this way they are searching. Instead of looking up and out as we might look at the sky or at the sea, the recordings look down and in. Listening to the earth becomes a kind of time travel, we hear deep echoes of previously untold histories, the geologic past as it carries forward like radio waves into space. In searching this deep we are also trying to see ahead. This project creates a new space, one in which we look to the resonance of rocks as soothsayers. The site of listening becomes a place to ask questions even as we struggle to divine the answers.

The Records hold two recordings each, one on each side. The recordings were made in a remote geyser basin within Yellowstone National Park’s Super Caldera. The caldera, a giant collapsed volcano, has a magma pool that sits just a few thousand feet below the surface, powering the area’s hydrothermal landscape.

This audio evokes the organic: coursing blood, a beating heart, steady breath. However, it belongs to a system so large as to be indifferent to organic needs. The shape is striated, like layers of sediment. In listening, as the sound drones on surrounding us, we are invited to sift through the acoustic strata, sinking into an alternate space. There is an anxiety here in the deepest layers of the infrasonic. It stems from cataclysm and the latent image of eruptive volcanoes and fractured earth, of burial but also a distant memory of birth. These recordings come from a place inaccessible and inhospitable to our bodies, and in this way they are searching. Instead of looking up and out as we might look at the sky or at the sea, the recordings look down and in. Listening to the earth becomes a kind of time travel, we hear deep echoes of previously untold histories, the geologic past as it carries forward like radio waves into space. In searching this deep we are also trying to see ahead. This project creates a new space, one in which we look to the resonance of rocks as soothsayers. The site of listening becomes a place to ask questions even as we struggle to divine the answers.

The Records hold two recordings each, one on each side. The recordings were made in a remote geyser basin within Yellowstone National Park’s Super Caldera. The caldera, a giant collapsed volcano, has a magma pool that sits just a few thousand feet below the surface, powering the area’s hydrothermal landscape.

None of these recordings are sounds that can be heard above ground. Instead, we’re listening to the gurgle and pop of water boiling below the surface, the thud of steam pushing through vents and a steady low rumble that comes from somewhere and nowhere deep within the earth.

Each record is also a custom made map, rendered from disparate USGS datasets that detail the geology of the park. Each map is unique. The differing colors and markings depict rock type, geologic age, the direction of ancient lava flows, rivers, lakes, subterranean faults and geothermal hotspots. Each face is a geologic portrait of the caldera, the rim of which is shown on every disk. Flipping the records turns the map from day to night. In this way, each record is also a spinning portrait of the earth.

The Permian Recordings

at LAXART

This project, exhibited at LAXART, is shown along side Karen Reimer’s quilted canopy of hand dyed indigo fabric. It is part of an ongoing series of work that use custom built infra-sonic subwoofers to listen to and feel seismic sound recordings of the earth.

The Permian Recordings come from the Permian Basin, a section of West Texas known for the volume and density of oil and gas extraction near the towns of Midland and Odessa. The permian layer, which gives the region its name, also demarcates the largest mass extinction in the history of the earth. Geologists have shown that at the end of the permian period, the atmosphere experienced a rapid rise in carbon dioxide, which resulted in global warming, followed by catastrophic climate change; an uncanny prehistoric echo of our present and near future.

At LAXART, a subterranean recording of the oil fields in the Permian Basin played from openning until closing each day with out repeating. It was important to me that the recordings be long, too long to listen to in a single sitting. In this way, we experience the work in human sized fragments, excerpts of a longer continuum, determined by chance and the limits of our attention span. What you hear is completely dependent on the time of day you enter the gallery. The sounds unfold in real time just as they were recorded. You may catch the room-shaking sound of a drill bit spinning up and then back down again, a truck as it grinds along a gravel road, or the distant thud and clank of pipes as they are fitted into a drill tower. In one instance there is an audible train whistle, in another the faint and muffled voices of workers, but for the most part the sounds are inscrutable, open to interpretation, speculation and imagination. It is as though we were listening to the distant machinations of the world from very deep below the ground. In reality the microphones, coupled to the earth, sit just at the surface, gathering the subterranean reverberations that amass into the droning shuddering tones of an industrialized landscape.

The Permian Recordings come from the Permian Basin, a section of West Texas known for the volume and density of oil and gas extraction near the towns of Midland and Odessa. The permian layer, which gives the region its name, also demarcates the largest mass extinction in the history of the earth. Geologists have shown that at the end of the permian period, the atmosphere experienced a rapid rise in carbon dioxide, which resulted in global warming, followed by catastrophic climate change; an uncanny prehistoric echo of our present and near future.

At LAXART, a subterranean recording of the oil fields in the Permian Basin played from openning until closing each day with out repeating. It was important to me that the recordings be long, too long to listen to in a single sitting. In this way, we experience the work in human sized fragments, excerpts of a longer continuum, determined by chance and the limits of our attention span. What you hear is completely dependent on the time of day you enter the gallery. The sounds unfold in real time just as they were recorded. You may catch the room-shaking sound of a drill bit spinning up and then back down again, a truck as it grinds along a gravel road, or the distant thud and clank of pipes as they are fitted into a drill tower. In one instance there is an audible train whistle, in another the faint and muffled voices of workers, but for the most part the sounds are inscrutable, open to interpretation, speculation and imagination. It is as though we were listening to the distant machinations of the world from very deep below the ground. In reality the microphones, coupled to the earth, sit just at the surface, gathering the subterranean reverberations that amass into the droning shuddering tones of an industrialized landscape.

Infrasound and Architecture

These recordings bring into proximity two scales of time: the geologic and the biologic, expressing them not as irreconcilable scientific measures of change, but as part of a continuum. When played back into space, these ultra-low frequencies subtly (though occasionally vigorously) shake the building that contains them. In this project I imagine architecture as a bridge between the human and the geologic. I am fascinated by the point at which foundation touches earth, relating two fundamentally different concepts of time. Architecture is meant to be experienced in human time as the space we pass through and live within, and yet the ruins of ancient cultures are so often the defining ligatures that tie our lived experience to the past. The frequencies in these recordings are physical as well as aural. Their playback creates resonance that extends from ancient rocks, passing through the structures we’ve built, and on into our bodies. This linking of stone to flesh through the reverberations of architecture points to these larger terrestrial and climatic systems of which we are constituent parts spanning vast periods of time.

“Because a portion of this audio extends below the range of human hearing (the infrasonic), these recordings are felt as well as heard. When I first listened to the ground of West Texas, I could feel the reverberations of metal carbide bits grinding against 250 million year-old rock, the din of diesel generators, and trembling waves of heavy machinery moving across the landscape.“

Google Maps: Drilling fields outside

Midland, TX, 2018

Midland, TX, 2018

Photo credit: Stone Yu, 2019

Special thanks to Cameron Hu, Marissa Benedict, David Rueter, Stone Yu, and the support of everyone at the Galveston Artist Residency for help in developing this project.

Video shot and edited by Stone Yu, 2019

Fault Lines and Freeways

As exhibited in Psycic Plumbing at The Canary Test

Durational sound installation

Curated by Gan Uyeda

Reviewed in ArtForum

by Catherine Taft

Fault Lines and Freeways is an installation of a subterranean sound recording of Los Angeles, played back through transducers mounted to structures in the gallery. The piece was concieved for an exhibition at Canary Gallery [pictured above] a former store front in the garment district of downtown LA. With the help of the gallery, we collected coat hangers from local dry cleaners and re-populated the old clothing racks in the back room. Instead of listening/feeling the infrasonic sounds of the Los Angeles underground, as in The Permian Recordings and Volcanic Drift, the transducers play the sounds as vibrations through the racks and walls, shaking the hangers and the gallery.

Video shot and edited by Stone Yu, 2020